April 26, 2022 Ι Architectural Record

From its permaculture food gardens to neighborhood brick-making workshops, to robot-traced empty lot block party takeovers, the 2021 Chicago Architecture Biennial (CAB)— under the direction of artistic director David Brown—was very much at home far from the downtown space that hosted previous biennials. But this spring, the Biennial is making a triumphant return from some of Chicago’s most disinvested neighborhoods to the Beaux-Arts-style Chicago Cultural Center in the Loop. The Center’s newly opened CAB Studio will become a venue for exhibitions, programing, and youth and family activities that will give the biennial a year-round home for the first time.

Last year, the CAB paired designers with local neighborhood organizations on the West and South Sides of Chicago to develop permanent and semi-permanent installations, outlasting typical-flash-in-the-gallery exhibition timelines and diffusing the energy and expertise of an international group of designers into places where it’s needed most. These installations became forums for engagement with a broader public that’s often invisible to the design community, and the new CAB Studio will offer a place to keep these conversations going. “We have such a diverse audience,” says CAB director Rachel Kaplan. “Being in the communities last year, we were able to engage people who would probably never come downtown. But having the downtown location engages people who don’t really know much about what’s going on in the city, and so being able to have those two counterparts strengthens our program.”

The CAB Studio’s inaugural exhibition is as grounded in and site-specific to Chicago as the installations for which the biennial is known. Originally staged as two separate exhibitions at the 2021 CAB, Architecture of Reparations is the work of Riff Studio’s Rekha Auguste-Nelson, Farnoosh Rafaie, and Chicago native Isabel Strauss, and will be on view through the end of summer. The exhibit traces the legacy of displacement and urban renewal in the historically Black Chicago neighborhood of Bronzeville, where some of the canonical figures of American architecture were both perpetrators—deploying displacement as a segregation and economic development strategy—and victims.

To begin, a long table of historical photos, drawings, and planning documents explain how Bronzeville—the earliest home for Black people in segregated Chicago, known as the “Black Metropolis”—was disfigured and immiserated by urban planning and architecture. Twenty-six thousand people were displaced by redevelopment plans including Mies van der Rohe’s Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) campus, one of the most celebrated icons of modernism in the world. Redlined and segregated in an effort to contain the city’s burgeoning Black population, Bronzeville became an enticing target for private real estate speculators and their enablers across all levels of government, who saw in Mies’ plan for the IIT campus a chance to remove an “undesirable” population and reverse sliding real estate values with a new institutional—and intensely inward-looking—presence. IIT’s success didn’t translate to the rest of the neighborhood, and by 1947, the campus had consumed 65 acres of Bronzeville, with the shock and trauma of mass relocations echoing throughout the neighborhood.

Documentary photos in the exhibit focus on the Adler and Sullivan-designed church where Mahalia Jackson and others invented Gospel music. In 2006, fire consumed the building—an example of canonical architectural heritage destroyed by vacancy and the systemic hollowing out of a community. But equal weight is given to vacant lots and the work-a-day handsome red brick three-flats (small apartment buildings at the scale of a house with three units) that preceded them and continue to define residential Bronzeville. “For people who don’t understand the significance of addressing racist housing practices, they can attach to the fact that these [high-profile] buildings are lost,” says Strauss. “And for people who don’t care so much about the architecture, and care about the community, they can look to the fact that this process has been replicated throughout the United States, and we’re still dealing with it.”

The exhibition frames possibilities for reparations through an RFP written by Riff Studio. It centers on housing as a way to move past abstract sums of money that never seem high enough and to ground the conversation in concrete, material benefits. A loose confederation of responses to the RFP by emerging architects and students are both practical and poetic, offering houses, live-work spaces, parks, and gardens in models, plans, and sections. But many entries step away from residential interventions with more ephemeral ideas of what reparations can mean, including meditations on South Side cultural artifacts, collages, and enigmatic photography.

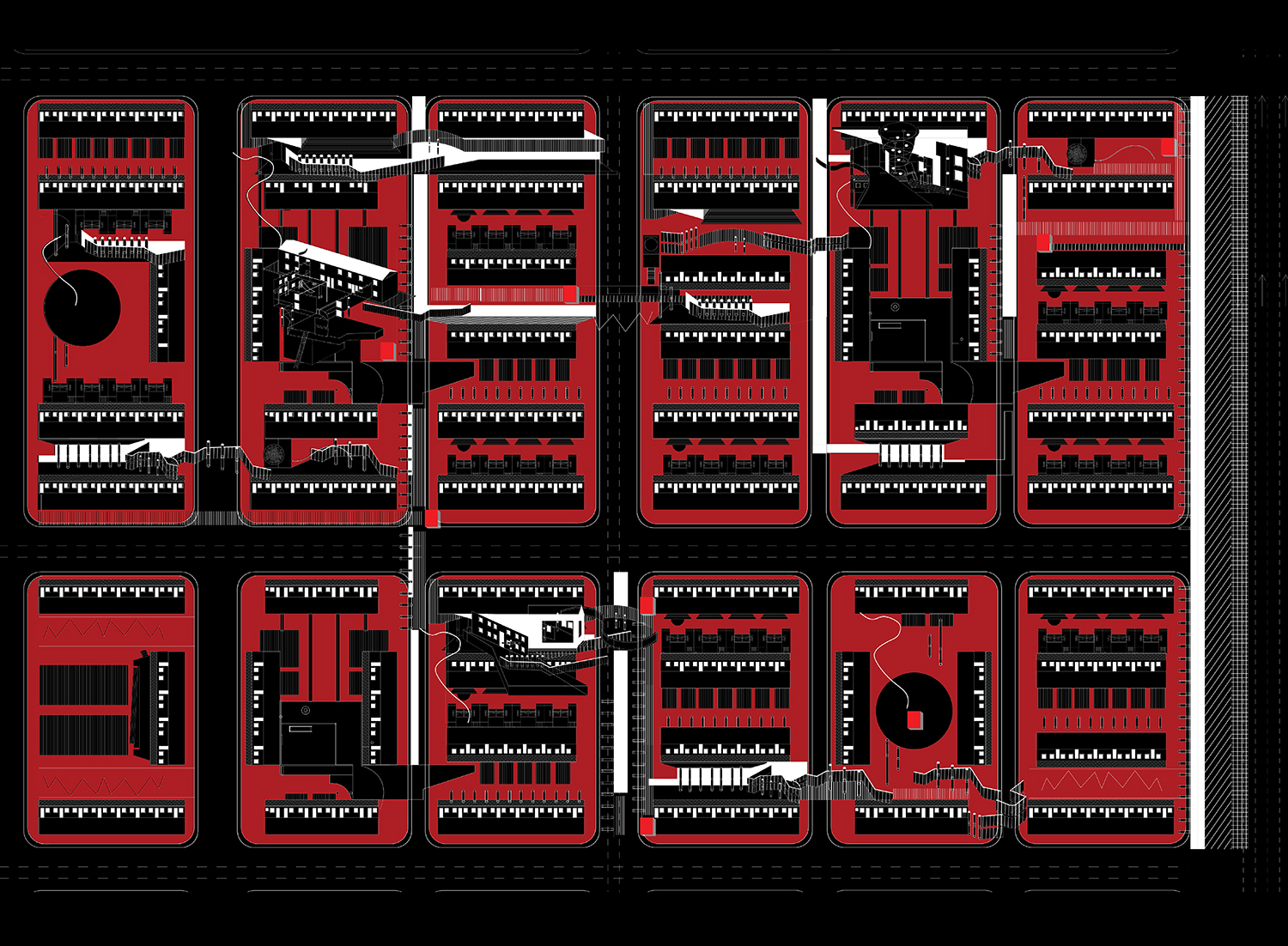

Afro-futurism and its inherent optimistic joy is a subtheme, and a collage by Omotara Oluwafemi presents a neon-submarine tableaux of wealth, power, and knowledge. One drawing offers a Zen koan—“Paradise is where your architecture takes the bullet instead”—written over intensely gridded, Miesian section drawings of Chicago Police Department substations. Plan drawings by Andrew Ngure of buildings composed entirely of thresholds, hallways, and other interstitial ephemera are a mildly sinister nod to the seemingly interminable debate about resolving the issue of reparations. Strauss’s own collages pull imagery from the mid-20th century photographer Richard Nickel’s pictures of Chicago architecture, working through broad spatial perceptions associated with domesticity (“Gaze,” “Pose,” “Rest”) if not specific programs. They’re frenetic, yet homey and familiar, and posit intimate moments of Black life within classic tropes of Chicago architecture, the most emotionally resonant response to the call for reparations.

All the while, a stereo plays a steady hip-hop and R&B soundtrack overlaid with audio clips from Malcolm X and local residents at city council meetings berating local officials for their racism and classism. The entire show is a kaleidoscope of painful realizations about how the built environment is made and whom it’s for—realizations that bruise the ego and expose the moral hypocrisies of generations of designers but nonetheless leave room for imaginative design solutions. “We can start with telling the story for what it is—telling the truth,” says Strauss. “And perhaps we have to do that with world-building.”

Riff Studio would like to see local organizations and neighbors in Bronzeville adopt and continue their work, to give it life beyond the exhibition hall. And Kaplan, for her part, hopes the CAB Studio can continue to offer a downtown platform to work like Architecture of Reparations.

She says the CAB is still formulating future programming for the CAB Studio, but that the space will likely host two exhibits a year. It could be most valuable as a place to showcase the work of the small neighborhood-based organizations with which the 2021 biennial partnered. “The program for the space is evolving, but at its core, the mission is to present innovative and daring ideas,” says Kaplan. “Exactly how that manifests and unfolds for each partner will be determined as we establish the long-term plan for the studio.”

If nothing else, Kaplan says, the CAB Studio can be a space to articulate the ongoing mission of the Biennial, and a place to explore and define its long-terms goals. With the fifth edition planned for 2023, Kaplan is “thinking about this as the first 10 years of a 100-year program.”