Landscape Architecture Magazine Ι October 2017

The first thing you notice is all the cars. The are a strange landscape divided by Jersey barriers and concrete retaining walls that carve up the site’s topography. Endless rows of cars are parked along its curving streets and in front of 62 three- and four-story barracks-style buildings that plod down the steep hill. It’s the first indication that this isolated, often forgotten section of the city is not that well connected to the thriving, upscale urbanism of San Francisco that surrounds it. “The beautiful green landscape, the Corbusian dream, just becomes parking,” says Gary Strang, FASLA, the founder of GLS Landscape | Architecture, the firm that was hired to radically reshape this place.

For Curteesha Cosby, who lives at Potrero, these parked cars are sometimes a refuge of last resort. When she’s walking her kids to school at 7:00 a.m. and hears gunfire, she hits the ground and rolls her children under them till it ends. She says she hears shooting nearly every day. She’s exhausted by Potrero. “I just want people to be happy and everyone to be safe,” she says. Her cousin was gunned down in the housing complex a few days before we spoke. Edward Hatter, the executive director of the Potrero Hill Neighborhood House, a nonprofit serving the area, tells me the community is waiting for the retaliatory violence that often follows shootings.

Potrero Terrace and Annex has long been one of San Francisco’s most dysfunctional large-scale public housing developments. Residents complain of mold and pests in their apartments. According to BRIDGE Housing, the nonprofit developer working at Potrero, violent crime is five times the city’s average, a particularly heartless statistic in light of the fact that 25 percent of residents are unemployed, one third are disabled, and fewer than half have bank accounts. By the low standards of American public housing, Potrero is fairly integrated and has no racial monoculture, with African American residents, Latinos, and Asian Americans. But, says Hatter, “This area was a forgotten [place] for many, many, many years.”

He’s seen Potrero transition from a neighborhood of working class San Franciscans in the 1960s and 1970s to a community ravaged by crack cocaine in the 1980s, then buffeted by the dot-com boom and bust in the 1990s. Lately a cresting wave of gentrification has washed over the Potrero Hill area. But the area’s public housing has been left untouched.

Today Potrero Terrace and Annex is top of mind for San Francisco’s civic officials and affordable housing advocates. It’s to be “revitalized,” in the parlance of development, the latest phase of the city’s ambitious HOPE SF program. The vision for Potrero includes a plan to raze and rebuild, adding market-rate housing and a comprehensive landscape plan by GLS Landscape | Architecture. Strang’s efforts will connect for the first time, integrating it with the charming bungalows and stepped Victorian confections just blocks away. It will also use open space as a way to bridge the gulf between longtime residents and the affluent newcomers who will help subsidize the affordable public housing.

Strang hopes that the new arrivals will accept Potrero and its current residents as their neighbors, though current public housing residents are wary that this will actually happen. “I feel that as the demographics change on Potrero Hill, the conversation is getting better,” he says. “There’s a lot of local pride, especially as developers and other people start discovering [this] neighborhood. People get protective.”

Jeris Glover has lived at Potrero for 46 years, raising her kids there as well as the children of others. She looks forward to when it will look “just like the rest of the hill.

“It’s going to change,” she says, “and there has to be a change.”

—

The Potrero Terrace and Annex, built in 1941 and 1954, respectively, were made to house shipyard workers employed on the bay, just to the east. They were racially integrated, and their residents were solidly working class, but the buildings were not great exemplars of design. “Designed by civil engineering,” says the architect Fred Pollack. “What’s the simplest way of throwing boxes on a hillside and doing the least grading?” His architecture firm, Van Meter Williams Pollack, did a new master plan for the site and is designing the first phase of its redevelopment, a 72-unit building that began construction in January, set to be complete next year.

Potrero Hill has a meandering suburban feel. Uniform, breadbox-shaped apartment buildings march down the curves of the hill like the ridges on a fingerprint, putting an abrupt halt to San Francisco’s relentless (if somewhat improbable given the city’s topography) street grid. There are wide lawns, but little space to be programmed for an organized public use.

Strang’s plan will tear out these meandering streets and connect the 38-acre site to San Francisco’s street grid, and add a network of small and large park spaces. In the process, it will regrade approximately 286,000 cubic yards of earth (the equivalent of six U.S. Capitol rotundas), and add another 98,600 cubic yards of soil. It’s a massive feat of earthworks on an extreme site that has made Strang revise his definition of what landscape architecture can be. All said, Strang will weave the Potrero plan through slopes of 20 percent, across a site that increases in elevation by 225 feet, offering spectacular views to rich and poor alike. “We come to landscape architecture with the idea that we’re working with plants and soil, and that it’s a horticultural undertaking. But when you get into a site that is this intense,” says Strang, who’s an architect as well as a landscape architect, “you realize that it’s literally about the architecture of the landscape.”

This is most apparent in the sets of pedestrian stairs that span the steepest blocks at Potrero; the primary north-south axis of Connecticut Ave. north of 25th St., and a smaller stair to the east along 23rd St. Careful refinements of the city’s historical pedestrian street stairs (“some of the most cherished places in San Francisco,” says Strang), Though it’s how the city’s original pedestrian stair streets were done, a 30-foot wide stairway parading resolutely in one direction would have been “a little bit overly monumental for the time that we’re in,” says Strang. “We’re really trying to create a more intimate and human-scaled experience, and to make sure the circulation doubles as outdoor space, so that each landing is a place to stop and sit, facing every cardinal direction. It took a lot of effort to make them buildable, give them spatial logic, and also make them green enough [so] that people want to spend time there.”

If these spaces are successful, Potero will be a topographic playground—literally, in the case of the 23rd St. stair, where a concrete slide will flow downhill, following the ground plane. “Having viable open space on really steep slopes is kind of new territory,” says Strang. “There have always been hilltop parks in San Francisco. This is not a hilltop park. This is a hillside park. It’s broadening the definition of what landscape architecture is.”

Much of the site’s intense topography is made up of a vein of serpentine rock that runs across the peninsula. This oddly rock was one of Strang’s most intense constraints, as its high magnesium content inhibits plants from absorbing and metabolizing nutrients, essentially dwarfing them, and its density prevents predictable and steady infiltration of rainwater. As such, many of the plants selected have to survive a trifecta somewhat unique to Potrero: serpentine-resistant, drought resistant, and tolerant of poor drainage. This is especially true of the trees that line both pedestrian and vehicular streets, like red flowering gum, eucalyptus, ginkgo, and the palm trees planted as accents at intersections. (Beyond trees, the definitive planting list hasn’t yet been determined.) Because of the sheer inclines, rainwater on site moves fast, and the serpentine rock below ground makes moisture harder to deal with once it’s infiltrated. Water that enters the ground through “cracks and crevices can pop up elsewhere, and you don’t really know where [it’s going],” says Strang. “Ultimately, that led to a strategy where we’re controlling more of the water on the surface.” This includes green roofs, planters, cisterns, a lack of permeable pavemening systems, and rain gardens in the new parks with liners that redirect water into storm drains.

It’s the second time that Strang has had to plan a public housing landscape amidst inhospitable geology. At the Hunters View HOPE SF site, Strang took what was an even more isolated and dilapidated public housing development and reorganized its landscape on top of unforgiving serpentine slopes. The recipient of a 2011 ASLA Honor Award in Analysis and Planning, Strang’s plan also reconnected the neighborhood to the city’s street grid where possible, and scattered a series of small parks across the site, like the oval park that dramatically orients views northward, towards San Francisco’s skyline. It’s attracted prominent Bay Area architects like David Baker to the site, which was previously the city’s most notoriously dysfunctional. , but it’s still planned,. But today Hunters View’s rich Cor-Ten steel finishes, cozy courtyards, carefully curated views, and mild Italian hill town sensibility signal that Strang already knows how to set the table for a vibrant public realm to emerge.

There are currently about 600 units of housing at Potrero, but the new development promises more than 1600 dwellings, more than doubling density in buildings up to seven to eight stories. Just about every element of the Potrero plan hinges on this increased density. With a strong housing market and a history of cheek-by-jowl living, “you can achieve multiple goals,” says Dan Adams, an architect and director of real estate for BRIDGE Housing, the nonprofit developer in charge of Potrero’s transition. “You can preserve the existing public housing, you can add more affordable housing, and you can bring market rate housing on at the same site.”

With the additional density, residents won’t have to be moved far away to alternative housing, or take their chances with a Section 8 voucher on the private market while their old home is demolished and their new one is being built. At Potrero, the first new building (going up on a vacant site) will house 53 of the 86 households whose homes are being demolished in the first phase of construction. (Nineteen units in this building will be designated as lightly subsidized affordable units.) The remaining current Potrero units will be rehoused in existing, vacant units on-site. There will be a broad mix of bedroom, says Adams, with predominately 1,2,and 3 bedrooms, with a few studios and 4 bedroom units. The goal is to choose bedroom number sizes by meeting the needs of the existing population at Potrero, so the final selection will be determined phase by phase.

After decades of a relatively uncrowded landscape, current residents are wary of this denser housing. “I feel like we’re going to be crunched up,” and placed “in a canyon,” says Cosby. Residents like Glover say they’d prefer single family homes, and she and Cosby both voiced understandable concerns over the security in quasi-public spaces such as the lobbies in apartment buildings.

Cosby, who works cleaning office buildings, is slated to move into her new home at Potrero soon, but says she would prefer to move away. She says she’s mildly hopeful that the new Potrero could be a better place, but is impatient for it to arrive. “It ain’t gonna happen overnight,” she says. “We know that already.” Most people who stay in Potrero, she says, do because they “don’t have anywhere else to go.”

The HOPE SF program itself is a result of not having anywhere else to go. In 2005, the San Francisco Housing Agency was staring at a , with annual federal funding set to provide only $16 million. With federal money dwindling (the landmark public housing privatization program HOPE VI had its funding discontinued after 2010) and a growing crisis of housing affordability, San Francisco could only depend on itself. HOPE SF, which began building in 2010, is mostly locally funded, gathered from bonds and a dedicated trust fund taken from the city’s general revenue. All told, HOPE SF aims to redevelop 3,000 to 3,500 units of existing public housing on four sites including Potrero.

The program has a similar cast of characters seen in other developer-led public housing conversions. There’s the beleaguered and underfunded city agency, the shrewd private developers at BRIDGE, the progressive designer teams fighting through legacies of racism and poor urban planning, and suspicious residents that aren’t quite ready to believe all the promises being handed out. Yet HOPE SF still differs from past efforts nationwide.

“There was an explicit desire to learn from precedent,” says Adams. He’s referring to HOPE VI and other programs’ tendency to tear down housing and build back only a fraction of it, scattering the people who live there to find housing elsewhere with Section 8 vouchers, if they can get them. BRIDGE Housing was also careful to get to Potrero years in advance of construction, running community outreach and social programming.

HOPE SF has two rules that set it apart: No relocation off-site, and a guaranteed 1:1 ratio for unit replacement, enforced by a city ordinance. With these safeguards for residents, San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee has called HOPE SF a

In addition to the 600 public housing units at Potrero to be replaced, there will be 200 units lightly subsidized by tax credits targeted at people making 50 to 60 percent of the area median income. Additionally, there’ll be 800 market-rate units, either for rent or sale. Across a build-out BRIDGE hopes to be complete by 2026, the city plans to spend $750 million to $1.5 billion for everything at Potrero, and that’s excluding market rate housing.

“We have a lot further to go,” says Dan Adams. HOPE SF, he says, is a narrow answer to a narrowly defined problem—redeveloping and revitalizing the city’s existing public housing stock. He hopes it will allow those in public housing have a better place to live so they can stay in their community. “It’s not the answer to the question of– how do we provide affordable housing in San Francisco?”

And at Potrero, the city is rushing to meet the need for affordable housing by providing subsidized housing before market-rate units. “This isn’t a project that is basically run on the market-rate side, and we just happen to do the affordable [housing],” “The affordable [housing] is driving the whole project.” Developers like Bridge are mainly paid upfront with developer fees, and get relatively little from the sale of market-rate units. The city pockets the revenue from the sale of market rate units, which becomes subsidy for additional affordable housing.

It’s a template that starts by addressing current public housing residents’ needs first. But neighborhood activists are still disappointed in how the Potrero plan is playing out. At Potrero and other HOPE SF sites, not a single building will mix market-rate residents with subsidized residents. “That’s what I call the segregation of poverty,” says Hatter.

—

Recent research has cast serious doubt on mixed-income housing’s ability to transform the lives of public housing residents. When Chicago unleashed its Plan for Transformation to of dystopian high-rise public housing and build back mixed-income garden apartments and townhouses, the results achieved—after a traumatic upheaval—were decidedly modest. As documented by the Urban Institute’s Susan Popkin, the relatively small number of housing residents that made it back into these new communities didn’t get new jobs that vaulted them into the middle class. Their lives were not remade with the help of neighbors who taught them how to code. They did find themselves in neighborhoods that were safer and more stable. But proximity within architecture hasn’t been able to cross that final bridge.

And because Potrero is surrounded by affluence (a block away, a-three bedroom, three- bathroom house recently sold for almost $2 million) it’s already a de facto mixed-income community. So why not just build back with the same high level of density, but make everything affordable?

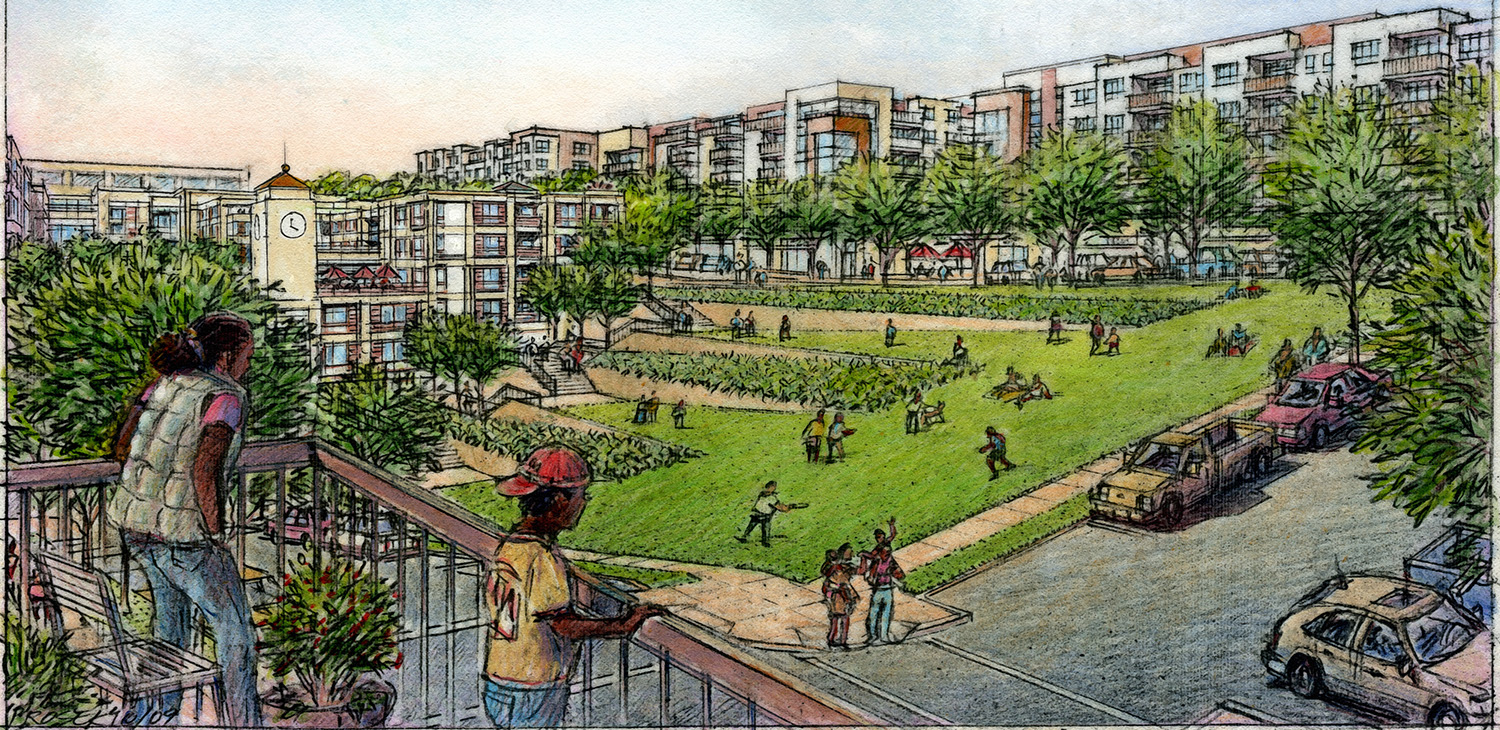

The current Potrero landscape has no hierarchy of public-to-private spaces. It’s a series of undifferentiated buildings and lawns. But the new plan offers a rich spectrum of landscapes, each suited to varying levels of neighborly intimacy. A large central park just east of the main north-south axis has a dramatically terraced lawn that will break down the hill’s steep topography. The main east-west axis, 24th St., will be oriented to pedestrians as the flattest street on the site, connecting to several new public amenities and retail spaces. (For those with limited mobility or disabilities, community services are located here.) There’ll be a small park (with the place-holder moniker “Squiggle Park) featuring with a sawtooth design that alternates terraced seating, lawns, and gardens filled with lilacs and poppies. And at the most intimate and private scale, interior courtyards planted with olive trees and coffeeberry will give apartment buildings their own dedicated public forum.

Across the entire plan, there is no singular space or monument that epitomizes the new Potrero’s ambitions for mixed-income living. Instead, Strang’s plan is a series of open space moments, connected to each other on the way to somewhere else. At the site’s northern edge, a series of small plazas ease visitors and residents into the neighborhood. The Squiggle Park connects to an existing local elementary school, and the Central Park is attached to the Connecticut St. pedestrian stair; itself a circulation path. The 23rd St. Stair leads to a nearby commuter rail station. Each bit of green space here will be a bit of a trail marker along a wider web. Strang says it was vital that “the spaces be connected into networks, instead of isolated green spaces.”

If a new sense of shared community and granular social connectedness forms at Potrero, it will be in these spaces, where people can meet as equals and learn about and from each other. There is no solution to affordable housing that is completely reliant on design at the expense of public policy. But landscape design may well be mixed-income housing’s best hope to fulfill its stated mission of uplift through spatial transmission of cultural capital.

“The landscape component,” Adams says, “is particularly critical when we think about encouraging interaction and social cohesion across different socio-economic groups.”

Strang is a bit less technocratic. “[Landscape] is the only neutral turf,” he says. “Whether or not the owners and developers can pull it off, I don’t know.”